Medtech Monitor: Abbott's Speedy CE Mark for Volt PFA Device and FDA Approves First At-Home Test for 3 STIs

Abbott Receives Early CE Mark for Volt PFA Device

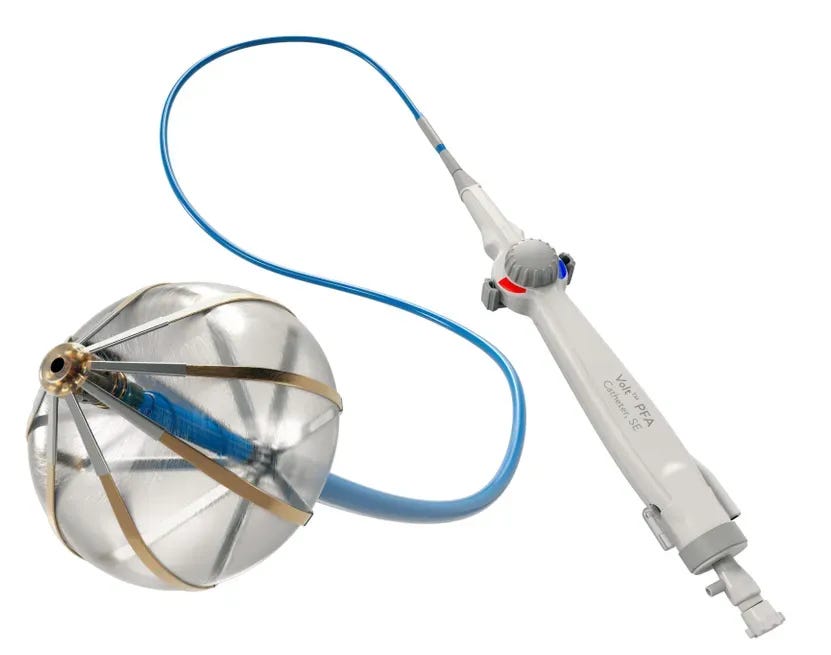

Abbott announced that it received CE Mark approval for its Volt pulsed field ablation (PFA) system ahead of schedule, marking a key milestone in its bid to catch up with competitors in the rapidly evolving electrophysiology space. The company has now initiated commercial PFA cases in the European Union, aiming to accelerate its rollout in the second half of the year. Initial adoption is focused on physicians who participated in the Volt clinical trials.

Abbott has been trailing Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Johnson & Johnson in the race to bring a PFA system to market. These companies have already established early momentum as the electrophysiology field shifts quickly toward PFA as a preferred method for restoring normal heart rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation. Boston Scientific has reported a surge in electrophysiology sales in 2024, driven by the strong performance of its Farapulse system. Medtronic also projected significant growth in its cardiac ablation solutions business. Meanwhile, Johnson & Johnson hit a temporary speed bump when it paused the rollout of its Varipulse device due to reports of neurovascular events, but has since resumed after determining the devices functioned as intended.

Abbott, now moving to close the gap, completed enrollment in its U.S. Volt study four months ahead of schedule and expects to wrap up 12-month follow-up later this year. The company has publicly stated it anticipates FDA approval in 2026.

Pulsed field ablation uses electrical pulses to selectively destroy the cardiac cells that trigger atrial fibrillation, with a reduced risk of damaging surrounding tissue compared to traditional thermal ablation techniques. Abbott claims its Volt system offers key differentiators, including improved visualization of catheter-to-tissue contact through a single-catheter approach. This design may reduce the number of therapy applications needed during procedures, potentially leading to better outcomes for patients.

CE Mark approval was based on strong clinical results, including a 99.1% rate of successful pulmonary vein isolation, the cornerstone technique in treating atrial fibrillation, across patients' targeted veins.

Analysis: The PFA Thunderdome remains the medtech headline of 2025, and Abbott is officially back in the arena. After Boston Scientific, who if we’re being honest was barely holding on to a “Big 4” spot in cardiac ablation back in 2023, took off by landing the first FDA approval for its Farapulse PFA system, it has been on a historic growth tear. Now we’re entering an Empire Strikes Back moment, with J&J, Medtronic, and Abbott all scrambling to get their hands on a piece of that sweet, sweet pulsed field momentum.

Abbott had looked like a late arrival to the PFA party, with no device on the market and little public traction. But the Volt system has gone from zero to hyperspeed in clinical development. Back in January, Abbott said it expected CE Mark "in the first half of 2025," which in corporate-speak usually means June-ish. So when they locked it in by March, it wasn’t just early, it was impressively early.

What’s even more jaw-dropping is their U.S. clinical trial enrollment: nearly 400 patients in just three months, finishing more than four months ahead of schedule. For context, Medtronic’s Affera system took about 12 months to enroll. PulseSelect needed nine. Farapulse? Fifteen. Abbott didn’t just beat the average, they smoked it.

This kind of speed gets Abbott back in the race, no question. But the clock is still ticking. Every month that passes without FDA approval raises the risk that Volt becomes a technical contender but a commercial also-ran in what is shaping up to be one of the most competitive cardiology markets in recent memory.

FDA Approves First At-Home Test for 3 STIs from Visby Medical

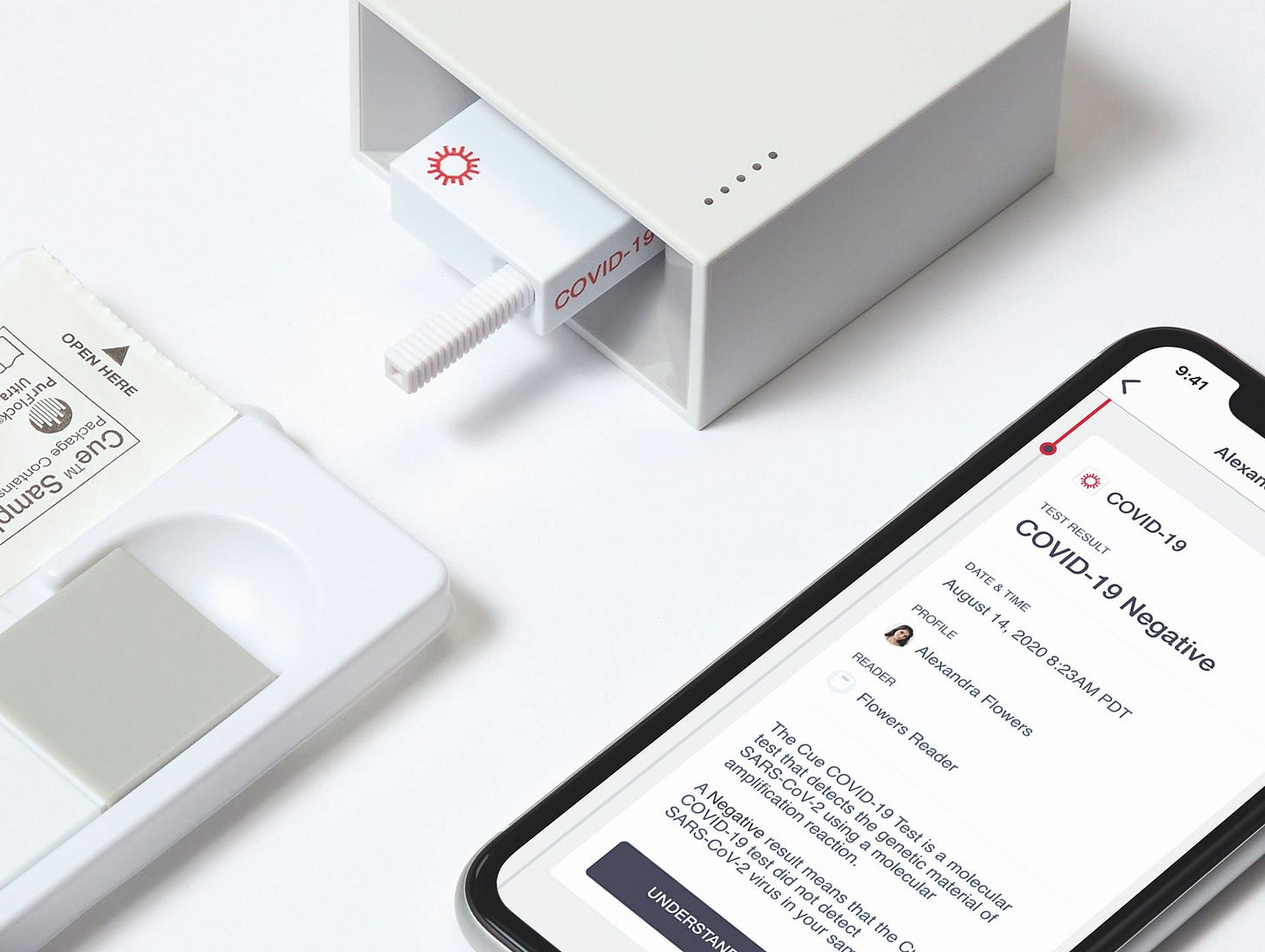

The Food and Drug Administration has authorized the first at-home test for three common sexually transmitted infections: chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis. The approval went to Visby Medical, which received a green light through the FDA’s De Novo pathway for its single-use, PCR-based diagnostic. The test allows women to self-collect vaginal swabs and run them on a compact, powered device, delivering results at home without the need for a prescription.

Visby operated largely under the radar for the first seven years of its existence, only stepping into the spotlight in 2020 when it received emergency use authorization for a COVID-19 test. By that time, it had already completed enrollment of more than 1,500 participants in a clinical study of its sexual health platform. The company raised $135 million in 2022 and secured 510(k) clearances for both the first- and second-generation versions of its test.

To earn the FDA's latest authorization, Visby demonstrated that its device accurately identified infections in both symptomatic and asymptomatic women. The test correctly detected 97.2% of positive Chlamydia trachomatis samples, with even higher performance for the other two pathogens. It hit 100% accuracy in identifying positive Neisseria gonorrhoeae cases and 97.8% for Trichomonas vaginalis. Negative sample detection was also near perfect across the board.

This clearance adds to a growing lineup of at-home sexual health diagnostics in the U.S. The FDA previously authorized the first at-home sample collection test for chlamydia and gonorrhea in 2023, followed by the first at-home syphilis test in 2024. According to the CDC, more than 2.4 million cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia were diagnosed and reported in the U.S. in 2023. Trichomoniasis, caused by a protozoan parasite, is the most common nonviral STI worldwide and affects an estimated 2.6 million people in the U.S. alone.

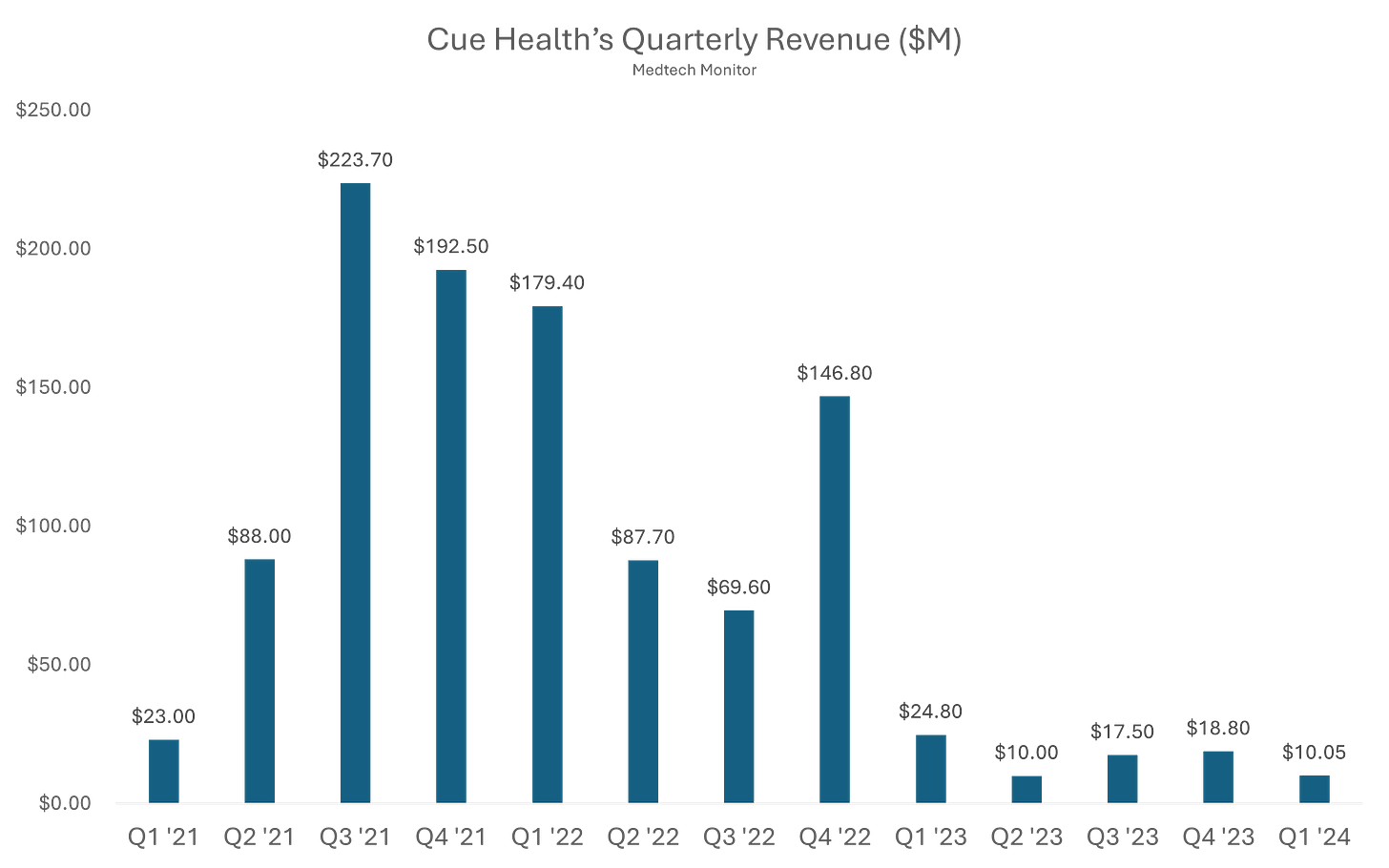

Analysis: Alright, we’ve got another company taking a shot at making at-home diagnostic testing a viable business model. No easy task. Anyone remember Cue Health, or at least the NBA bubble?

Cue Health launched back in 2010 with a bold mission: bring lab-quality diagnostics into the palm of your hand. For nearly a decade, it toiled in relative obscurity, quietly building a molecular testing platform. Then came COVID-19, and suddenly Cue was not just relevant, it was essential. In the chaos of 2020, the company rolled out a sleek, smartphone-connected test that could detect COVID with lab-level accuracy in about 20 minutes, right from your kitchen table. Silicon Valley and Washington paid attention.

The Department of Defense handed Cue a major contract. Google partnered with them to supply tests to employees. Even the NBA jumped in, using Cue’s test to screen players and staff during the league’s bubble season. For a brief, shining moment, Cue Health was not just a diagnostics company. It was the diagnostics company. By 2021, it had gone public in a $200 million IPO, landed a $2.3 billion valuation, and generated more buzz than most medtech startups dream of.

But the post-pandemic world had other plans. As demand for COVID testing dried up, so did Cue’s cash flow. The company had bet big, really big, on a single virus and a single test. It tried to pivot into broader diagnostics like flu and fertility, but time was not on its side. In May 2024, the FDA issued a brutal warning about unauthorized changes to Cue’s COVID test and advised the public to stop using it.

By June 2024, Cue Health had filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy and laid off its remaining employees. The same company that once teamed up with the NBA and claimed a front-row seat in the COVID response quietly exited stage left. Cue’s rise and fall is a textbook pandemic-era arc: fast ascent, sky-high expectations, and a sharp crash once the world moved on. Disrupting diagnostics is hard, and even the most high-tech test cannot save you from a one-product business model.

To understand why disrupting diagnostics is so difficult, it’s worth zooming out and looking at how the existing system actually works. In the U.S., the diagnostic testing market is built on a reimbursement-driven, business-to-business foundation. Companies like Quest Diagnostics, Labcorp, and BioReference primarily serve hospitals, health systems, and physician practices. Their revenue comes not from patients, but from billing insurance, whether Medicare, Medicaid, or private payers. A doctor orders a test, Quest or Labcorp runs it, and the lab sends the bill to insurance. Patients pay little, maybe a co-pay, maybe nothing at all. Price sensitivity is practically nonexistent, and no one is shopping around for a better deal.

But it’s not just about Quest and Labcorp. Behind the scenes, there’s a whole other layer powering the lab world: the classic IVD giants like Roche, Abbott Diagnostics, Siemens Healthineers, and BioMérieux. These companies within their Core Lab segments do not sell tests to consumers. They sell analyzers, reagents, and software to labs and hospitals, massive high-throughput machines that run thousands of tests a day. They build their businesses on long-term service contracts, locked-in reagent supply chains, and integration into hospital systems. When a hospital buys a Roche cobas or an Abbott Alinity platform, it is not buying a gadget. It is signing up for years of embedded infrastructure.

That makes Visby Medical’s approach fundamentally different. Visby is not trying to supply hospitals or outfit high-volume labs. It is trying to replace that entire system with a palm-sized PCR machine designed to be used on your bathroom counter. Instead of selling into a procurement committee or clinical lab director, it is targeting individual consumers or primary care providers. There is no LIS integration, no reimbursement engine, no on-site technician. Just a cartridge, a swab, and a result.

At-home diagnostic startups like Visby, Lucira, and Cue are trying to create a new model entirely: direct-to-consumer, no insurance, no doctor required. That sounds great in theory. But in practice, it introduces friction. Most consumers are not in the habit of spending $75 to $200 for diagnostics, especially for tests they can get for almost nothing through insurance. Without coverage, these companies have to convince people to change behavior and pay more at the same time. That is a tall order.

There is also the matter of trust. People still lean on physicians for diagnosis, especially for emotionally sensitive or complex issues like STIs or chronic disease. Even if the test is accurate, there is anxiety around using it correctly, understanding the result, and figuring out what to do next. A positive test from Visby may give you an answer, but it does not get you treatment. That part is still on you.

Trying to disrupt diagnostics from the at-home side is like installing a sleek rain showerhead without touching the building’s plumbing. It might look great, but nothing is coming out unless you are connected to the system. Patients say they want convenience, but most will not trade a five-minute clinic visit for a $100 test they have to run, interpret, and act on themselves. They are used to handing over an insurance card, not a credit card. And they still trust their doctor more than a blinking cartridge.

Unless at-home diagnostic companies pull off a radical pivot or team up with the big players like Quest, Labcorp, or even the IVD giants themselves, they are basically speedrunning to the startup graveyard. The current playbook, sell expensive tests direct to consumers, bypass the entire reimbursement system, and hope for a behavior shift, is not a go-to-market strategy. It is a slow-motion implosion. Disruption might be sexy, but in diagnostics, survival usually comes down to a billing code and a well-connected friend in the payer network.